|

|

|

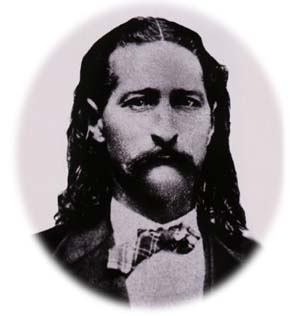

JAMES BUTLER HICKOK, the renowned "Wild Bill," remains perhaps the most

famous of all Western gunfighters. His exploits as a Civil War operative,

frontiersman and peace officer have been celebrated often in print, in

movies, and on television. But, despite all this attention through the

years, we know very little about the man himself. Vintage photographs,

haunting and mysterious, span the mist of time.

We wonder, who was Wild Bill Hickok?

JAMES BUTLER HICKOK, the renowned "Wild Bill," remains perhaps the most

famous of all Western gunfighters. His exploits as a Civil War operative,

frontiersman and peace officer have been celebrated often in print, in

movies, and on television. But, despite all this attention through the

years, we know very little about the man himself. Vintage photographs,

haunting and mysterious, span the mist of time.

We wonder, who was Wild Bill Hickok?

Hickok wanted neither notoriety nor love, and he had no romantic

relationship with Martha Jane Cannary, the famed Calamity Jane (see the

August 1994 issue of Wild West for more on her). He just wanted to return

to his new wife with some money in his pocket, as evidenced by a portion of

his letter from Deadwood on July 17, 1876:

Hickok wanted neither notoriety nor love, and he had no romantic

relationship with Martha Jane Cannary, the famed Calamity Jane (see the

August 1994 issue of Wild West for more on her). He just wanted to return

to his new wife with some money in his pocket, as evidenced by a portion of

his letter from Deadwood on July 17, 1876:

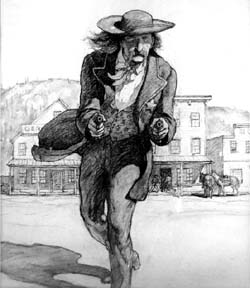

In order to place the Smith sculpture on display, the Adams Museum contracted with David and Greg Akrop of Deadwood Granite and Marble Works who attached the broken legs to the torso and made a base to stabilize the statue. Somewhat reminiscent of the Venus de Milo with its missing body parts, one cannot help but be reminded of Hickok's parting words, "The old duffer -- he broke me on the hand." While the Smith "Wild Bill" stands as a reminder of Hickok's status as a western folk hero, it also serves as a sad display of the results of vandalism.

Anyone who may know the whereabouts of the missing pieces of the statue are urged to contact the Adams Museum's director. The Adams Museum encourages visitors to enjoy Deadwood's monuments with your eyes only.

In order to place the Smith sculpture on display, the Adams Museum contracted with David and Greg Akrop of Deadwood Granite and Marble Works who attached the broken legs to the torso and made a base to stabilize the statue. Somewhat reminiscent of the Venus de Milo with its missing body parts, one cannot help but be reminded of Hickok's parting words, "The old duffer -- he broke me on the hand." While the Smith "Wild Bill" stands as a reminder of Hickok's status as a western folk hero, it also serves as a sad display of the results of vandalism.

Anyone who may know the whereabouts of the missing pieces of the statue are urged to contact the Adams Museum's director. The Adams Museum encourages visitors to enjoy Deadwood's monuments with your eyes only.